By creating an account, I agree to the

Terms of service and Privacy policy

Choose your country and language:

Africa

Americas

Asia Pacific

Europe

IIt was an act that had played out many times in South Africa: a forced removal. In 1904 the bubonic plague broke out in the town centre, in an area known as Brickfields. Once the brick makers had been removed 25km south, to Klipspruit, the area was fenced and razed to the ground. And so Soweto was born.

In time Klipspruit was settled by a bohemian group of people - whites, coloureds, Indians and a sprinkling of Chinese joined the original black people. An Afrikaner had a dairy farm in the area, where the pastures were rich.

So it seemed natural that, 51 years later, in 1955, that nearby Kliptown was where several thousand people from around the country gathered to ratify the Freedom Charter, a document setting out the ordinary aspirations of black South Africans for equal rights in the land of their birth. It was an atmosphere described by Nelson Mandela in his book Long Walk to Freedom as “serious and festive”. Fifty years later, on 27 June 2005, Mandela was there again, in his capacity as retired president of a democratic South Africa. This time the gathering saw the opening of the grand and symbolic Walter Sisulu Square of Dedication, to commemorate the historic day in 1955.

TToday Soweto is a vast neighbourhood, where more than one million people live. It’s an area of 200km², with over 355 000 households. It was only in 1963 that it adopted the name Soweto, an acronym for South Western Townships.

It’s a place of contrasts: with mansions, and almost over the road, overcrowded iron shanties. It’s where some of the country’s most illustrious struggle heroes lived: Mandela, with his first wife Evelyn and second wife Winnie, Walter and Albertina Sisulu, Charlotte Maxeke, Lillian Ngoyi, and many others.

The township has seen waves of occupation, as black people entered the city, seeking jobs and a place to live, after being pushed off the land. In the 1930s Orlando was laid out, a “model native township”. It was to have a green belt, with parks, roads and houses with gardens. But it didn’t happen: rows of identical matchbox houses with no electricity or plumbing were built, stretching into the distance in monotonous regularity, a pattern of settlement throughout the township.

Houses were built in fits and starts by the city council, but the demand always outstripped the supply. Areas became squatter camps, as people were moved from inner-city slums, or suburbs where whites wanted to live. Heroes emerged. In the 1940s James Sofasonke Mpanza, a striking figure on a horse, led some 20 000 people to vacant land, where they erected their hessian or sack shacks.

IIn the 1950s Meadowlands was created. Some 65 000 people from the vibrant, ghetto suburb of Sophiatown in “white” Johannesburg were removed to the new suburb in Soweto. Resident Nelson Botile, quoted in The Joburg Book, said: “The walls were not plastered, they were rough, and the floor was just grass. It was not cemented. My father started plastering the house once we were inside. The houses had no taps. We didn’t have sewage - we had what was called the bucket system and we had these people coming in the night to remove the sanitation. The streets were not tarred and they had no names. The houses only had numbers.”

In 1974 an intriguing set of clay sculptures and buildings was created in the heart of Soweto, called the Credo Mutwa Cultural Village. The village in Central Western Jabavu was completed by artist, author and traditional healer Credo Mutwa. The large painted sculptures of human and animal figures have a mythical and fearsome quality, depicting African culture and folklore.

Perhaps Soweto’s most enduring moment was the June 16, 1976 uprising, which saw schoolchildren march against the imposition of Afrikaans. The drama played out on the streets of Orlando West, when police met thousands of marching children. Police opened fire, and many died on the way to hospital, or in the corridors of Baragwanath Hospital. The township was an uneasy battleground the next morning, with burnt-out vehicles strewn everywhere, and smoke rising from smouldering buildings.

IIt was the start of the end of apartheid. By the beginning of the 1980s black South Africans were mobilising around the country, and by 1990 apartheid had been brought to its knees. Mandela came home from Robben Island to his humble house in Vilakazi Street, if only for 11 days. The house is now one of two museums in the township. In 2002 the Hector Pieterson Museum was opened. It commemorates 12-year-old Hector’s ultimate sacrifice on June 16, the first child to die by a police bullet. He is buried in Avalon Cemetery, where many of apartheid’s victims are buried.

In the last 20 years Soweto has come of age. All roads have been tarred, thousands of trees have been planted, shopping malls have opened, the first gym has appeared, and the colourful Soweto Theatre in Jabulani is now the playground of Soweto’s artistic talent. Orlando Stadium, with its nearby Olympic-sized swimming pool, was rebuilt for the 2010 Football World Cup. There’s a golf club and an equestrian centre, owned by Enos Mafokate, who represented South Africa in the 1992 Olympic Games. There is now an annual marathon, a wine festival, and the Soweto Derby football match. Soweto is home to football clubs Kaizer Chiefs and Moroka Swallows. Successful Soweto businessmen include Richard Maponya, Joburg’s mayor Herman Mashaba and Nthato Motlana, among others. Kwaito and Kasi Rap, a form of hip-hop, originated in Soweto. The township has a television channel, Soweto TV. It also has a gospel choir and a string quartet.

“Soweto is a place full of love and unity and people here look out for each other,” businessman Thabo Moagi told The Guardian in 2015. “Soweto has everything I need. The people. The shops. The culture.” None of this means that Soweto is not affected by crime, but Sowetans are warm and friendly, and always ready to party.

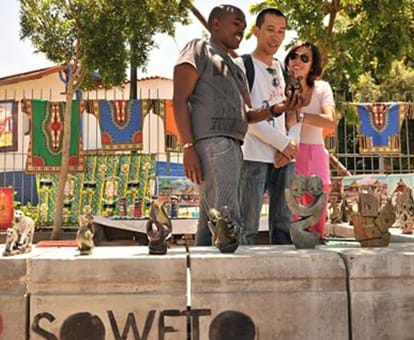

Soweto

AAbout the author

Lucille Davie has a BA Education degree and a Tesol English 2nd Language Certificate. She taught for 20 years and was a journalist for 19 years. For 13 years she wrote on the history and heritage of Johannesburg for the joburg.org.za website, and on a broad range of subjects for mediclubsouthafrica.com. For three years she wrote a monthly column for the Saturday Star, entitled Jozi Rewired. A selection of all these articles is available on lucilledavie.co.za

In 2014 she wrote a book for Johannesburg City Parks & Zoo, entitled A Journey Through Johannesburg’s Parks, Cemeteries and Zoos. She now conducts Joburg tours, teaches English to expat children and adults, and writes about Jozi people and other Jozi stuff. Her interests include reading, writing, mountain biking, swimming, and travelling. She has completed four Dusi Canoe Marathons, ridden the Cape Argus Cycle Tour, and climbed Mt Kilimanjaro.

Related articles

|Terms and conditions|Disclaimer|Privacy policy|Terms and Conditions-Valentines Campaign