By creating an account, I agree to the

Terms of service and Privacy policy

Choose your country and language:

Africa

Americas

Asia Pacific

Europe

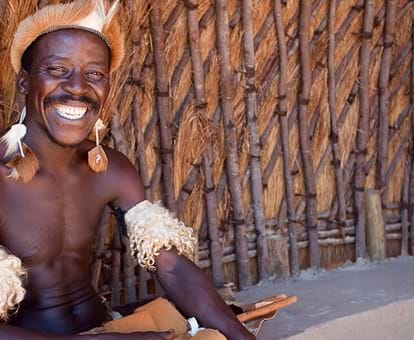

TThe Zulu-speaking people are descendants of the Iron Age communities of Southern Africa who cultivated the soil and kept livestock. They inhabited the well-watered region of Southeast Africa, the interior in the Highveld, and the territory between the Drakensberg and the Kalahari borderland. They had mixed economies growing crops in a harsh environment. Temperature, topography and rainfall influenced the productive characteristics of the soil. Warm temperatures and high rainfall in the coastlands and lower river valleys permitted long growing seasons, whereas the growing season became shorter as rainfall and temperature declined in the interior.

Farmers adapted to these conditions by growing crops with different productive and harvesting characteristics. The most important crops that these societies grew before 1700 were millet and sorghum because they had the capacity to withstand drought and infertile soil conditions. During the 18th century, maize, a foreign product that the Portuguese had introduced into the region, replaced or coexisted with millet and sorghum. Maize had similar requirements to sorghum in planting, weeding and harvesting. It was, however, superior to sorghum in producing a higher yield of food per hectare, and was less susceptible to damage by birds.

CCattle were of symbolic and material importance to both the rulers and the commoners in the farming societies of Southeast Africa (including KwaZulu Natal) before the advent of colonialism. They were used for subsistence, exchanged for women as the lobolo (bride-wealth) and as gifts (tributes) to the ruling families, or distributed to the needy clients.

For example, the Zulu established a system of patronage known as ukusisa. In terms of this system, a wealthy Zulu man (umnumzane) loaned a few cattle to a poor person without a herd of his own. Each recipient of cattle through this practice was responsible for their care and got the right to milk them for nourishment and could keep some of their offspring when he returned or repaid the loan to the owner. There were several conservation advantages in these patronage relations. The livestock was spread over large geographical areas, which prevented complete decimation of the herds in the event of natural disasters such as drought or cattle diseases. Politically, firm allegiances and alliances were formed between the providers and recipients of patronage. Furthermore, the recipients of the favours took care of the wealthy men’s cattle.

The Zulu were not the only society to engage in this ukusisa practice. The Tswana used a similar practice to entrench social differentiation and establish large chiefdoms around the same period. The Sotho too had the practice known as mafias, which functioned along the same lines. Some commentators often refer to this as evidence of the existence of ubuntu (humaneness) in precolonial Southern African societies.

SSuccessful stock keeping depended on the use of a variety of grassland ecologies to maximise grazing potential. Sourveld in the coastal regions and highlands was palatable and nutritious in the spring and early summer only. Mixed grass in the transitional zones was grazed in the late summer, and the delicate sweet grasses of the valley floors were grazed during the dry winter months. During the periods of normal rainfall, cattle were moved about within a 20 mile radius, but they had to be moved further afield during times of drought. Drifting away to new territories was possible as long as there was unoccupied land. It came to an end when the population grew. This gave rise to conflicts and violent clashes over land. The fierce conflicts that erupted in Southeast Africa became commonly known as the Mfecane or difaqane. However, this analysis became a controversial issue, which generated fierce debate in late 20th century South Africa and was subsequently abandoned in academic circles.

Cattle were of symbolic and material importance to the Zulu kings as well. The distinctive white inyoni kayiphumuli (the bird which does not rest) was King Shaka’s own preferred breed. They had the milky hide and dark points at ears, muzzle, horns, hooves and eyes. Among the Zulu people, the colour white has spiritual and ritual significance. It is associated with purity, harmony, coolness and the absence of pollution. White is the colour of the ancestors, diviners and protection against lightning. As a result of this significance any white calf born in the byre of a commoner was automatically given to the king.

The name inyoni kayiphumuli possibly refers to the egrets (tick birds) that follow them everywhere.

TThe Nguni cattle, with their characteristic diversity of tones and range of combinations, which gave them a distinctive resemblance of a flock of multi-coloured birds when they were grazing on the pasture, were another important breed of cattle within the Zulu kingdom. The shades of red, brown, dun and yellow made them appear enamelled in the light. Cattle were of symbolic and material importance to the commoners as well. The Zulu expression “umnumzane ubonakala ngesibaya sakhe” (the man’s social status is seen by the size of his kraal) signifies the centrality of cattle as a form of wealth even among commoners. The larger the kraal, the more senior the man’s social status.

AAbout the author

Jabulani Sithole is a former lecturer in history at the University of KwaZulu-Natal, a position he held for 13 years. He holds a Master of Arts degree in History, and is a PhD Candidate at Wits University. He co-authored a book called Zulu Identities: Being Zulu Past and Present, along with Benedict Carton and John Laband. He has served as the KwaZulu-Natal Provincial Coordinator of the Liberation Heritage Route in the National Heritage Council, and former chairperson of the Albert Luthuli Museum Council. Jabulani currently writes and edits books and academic texts about Zulu history and culture.

Related articles

|Terms and conditions|Disclaimer|Privacy policy|Terms and Conditions-Valentines Campaign